LAMBERT CASTLE: THE HISTORY THEY DIDN’T TELL YOU – STRATEGIC OVERLOOK, PATERSON, NEW JERSEY

By Bernard Van Houten,

Stand on the terrace of Lambert Castle on Garret Mountain and look down.

You’re not just looking at a “nice view.”

You’re staring at the original power vantage point of Silk City — a stone command post built high above the mills, the smoke, the strikes, and the streets of Paterson.

Tour guides will give you the postcard version: Victorian mansion, art collection, wealthy silk baron, now a museum. All technically true.

But they usually skip the part that matters:

Lambert Castle was a strategic overlook — a literal high ground in a city built on industrial warfare.

The Mill Owner Who Built Himself a Fortress

Before Lambert Castle was an Instagram backdrop, it was called “Belle Vista” — “beautiful view.”

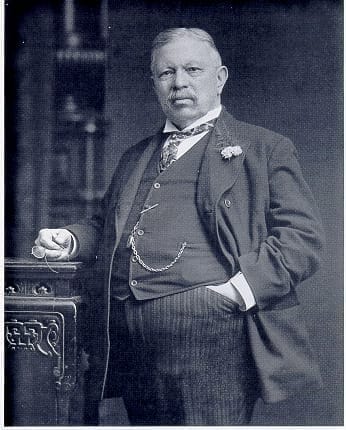

It was built in 1892–1893 by Catholina Lambert, an English immigrant who came to America as a teenager, made a fortune in the silk trade, and climbed all the way up from the factory floor to owning one of Paterson’s major mills.

Instead of settling for a mansion downtown like a normal Gilded Age rich man, Lambert did something else:

- He picked Garret Mountain, a basalt ridge that rises above Paterson and the Great Falls.

- He built in a castle style, with towers, crenellations, and thick stone walls more reminiscent of northern England than North Jersey.

- He positioned it so the house and later the observation tower could look down over the city, the rail lines, and — on a clear day — the Manhattan skyline.

On paper, it was a dream house.

In practice, it was a statement: I sit above all of this.

Why This Hill, Why This View?

To understand how strategic that choice was, you have to remember what Paterson was at the time.

Thanks to Alexander Hamilton’s Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.), the Great Falls of the Passaic had been turned into a power source that fed raceways, mills, and factories. Paterson went through waves of cotton, then locomotives and guns, and finally silk, earning its title as “Silk City.”

By the 1890s, the valley below Garret Mountain was:

- Packed with silk mills and dye houses

- Laced with railroad lines that would later become the corridors for Route 19 and I-80

- Full of dense worker housing — immigrants from Italy, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and beyond

Lambert didn’t just want a big house. He chose a position where:

- He could literally look down on the city whose labor paid for his lifestyle

- His tower and terraces gave him clear sightlines over the industrial landscape

- His home physically separated him from the workers whose wages he controlled

Was Lambert sitting there with binoculars, tracking every loom? Probably not.

But you don’t put a castle on the ridge above your own mills by accident.

Inside Silk City’s Private Gallery of Power

Lambert didn’t just build big; he built loud.

Inside Belle Vista, he assembled an art collection that today would read like a museum checklist: more than 400 paintings, including names like Monet, Renoir, and possibly Rembrandt, displayed in a purpose-built art gallery wing and later expanded spaces.

He kept adding:

- A 70-foot observation tower and summerhouse on the crest (1896)

- A large enclosed gallery for his paintings

- Gardens and greenhouses spilling down the mountain slopes

The guest list wasn’t subtle either.

President William McKinley and Vice President Garret Hobart visited the castle in 1898 – a U.S. president literally coming up the hill to the silk baron’s house.

That’s not just lifestyle. That’s branding:

You work in my mills. The President visits my house.

The Strike That Shook the Castle

Then came 1913.

The Paterson Silk Strike — 25,000 workers shutting down some 300 mills and dye houses for nearly five months — was one of the most intense labor showdowns in American industrial history.

The target? The silk mill owners — including the likes of Lambert’s Dexter mill, one of the businesses in the crosshairs of worker anger.

From the valley, workers rallied in places like the Botto House in nearby Haledon. From the ridge, Lambert stayed in Belle Vista, watching his industry convulse.

The official histories will tell you this:

- The silk industry declined in Paterson after the strike

- Dexter, Lambert & Co. struggled with debts and the aftershocks of the 1913 unrest

- In 1914, the firm was liquidated

- In 1916, Lambert was forced to auction off his art collection to cover liabilities

He kept the castle, but the balance of power shifted.

Silk City’s workers had marched, been arrested, beaten, and ultimately defeated — but the industry’s golden age cracked in the process.

The view from the tower didn’t change.

The meaning of what lay below did.

From Fortress to Sanitarium to Museum

After Lambert died in 1923, the estate didn’t stay a private castle for long.

- The building was sold to the City of Paterson, which used it as a tuberculosis hospital.

- In 1928, Passaic County acquired the property and folded it into the growing Garret Mountain Reservation as public parkland.

- By 1936, the Passaic County Historical Society began using rooms inside as a museum; over time the exhibits expanded until the castle became the society’s main home.

- In the 1970s, Lambert Castle was officially listed on both the New Jersey and National Register of Historic Places.

Today, the tour is mostly about architecture, décor, and local artifacts. On some days, you can still climb the tower and get that same sweeping view across Paterson, the Passaic Valley, and the New York skyline.

But for a long time, the story was sanitized:

castle, culture, “old money,” nice weddings, school trips.

The class war underneath the stone? Background noise.

What They Didn’t Emphasize: Geography as Power

Here’s the part that fits the real Silk City story — and the part that usually gets left as subtext.

- Location as a flex

Lambert picked a ridge that turns the entire city into a stage below him. Garret Mountain is a natural high ground overlooking a National Historic Landmark waterfall, major transport corridors, and the dense industrial grid of Paterson. - Architecture as messaging

A medieval-style castle on an American industrial ridge isn’t “just taste.” It’s a deliberate Old World power aesthetic dropped on top of New World labor. - Timing

The house goes up in the 1890s, right as Paterson hits peak “Silk City” intensity — and a couple of decades before the 1913 strike exposes just how explosive the factory floor has become. - Afterlife

When the industry and Lambert’s finances crack, the castle doesn’t disappear. It becomes county property — a reminder that the physical infrastructure of power outlives the people who built it.

Walk the terraces today and you can see:

- School buses in the parking lot

- Couples taking photos on the steps

- Highway noise from I-80 and Route 19 floating up from the valley

What you don’t always hear about is the line between:

- The mill owner on the mountain

- And the 25,000 workers in the streets below asking for an eight-hour day

The Strategic Overlook, Then and Now

So yes, Lambert Castle is:

- A restored Victorian mansion

- A county museum

- A nice Sunday outing spot

But it’s also something else:

A physical diagram of power in Paterson.

- The Great Falls powered the mills.

- The mills produced the silk.

- The workers kept the looms running and took the hits when they demanded better conditions.

- And up on the ridge, a silk magnate built a castle and tower to live above all of it.

Here at The Garden State Gazette, we don’t put sugar in our coffee.

We’re not saying Lambert had a war map on the wall and a telescope aimed at every smokestack.

We are saying this:

You don’t spend that much money, in that era, to build that kind of structure on that exact ridge — overlooking mills, rail lines, and a rising industrial city — without understanding exactly what the view is worth.

Lambert Castle isn’t just a pretty relic.

It’s Silk City’s original strategic overlook — and the stone proof that in Paterson, power has always liked the high ground.

Member discussion