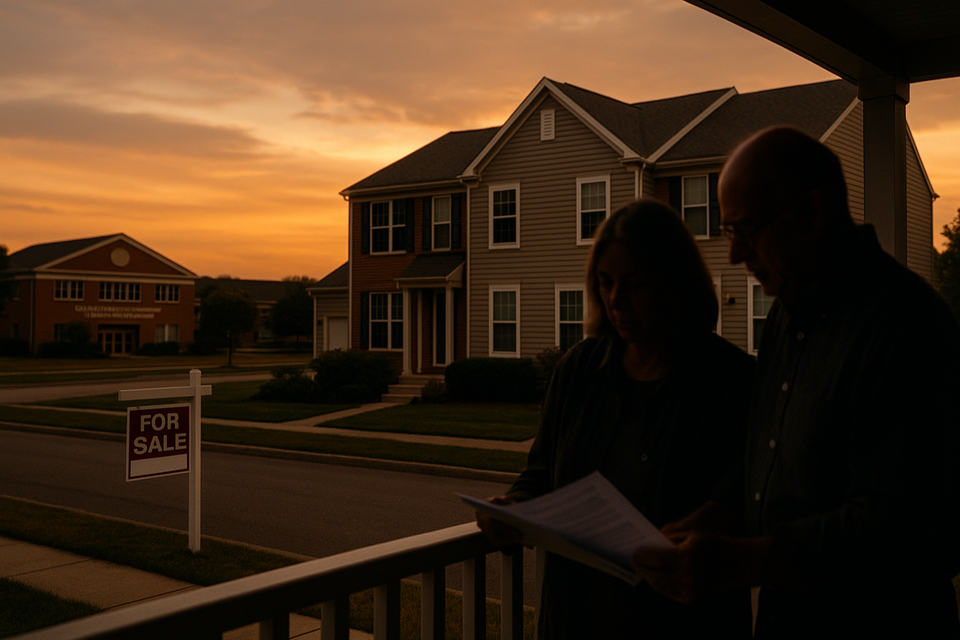

“We Did Our 30 Years. Now They Want 60.” Montgomery Homeowners Say New Affordable Housing Law Is Being Twisted Against Them

By The Garden State Gazette Staff

Editor’s note: For privacy and protection, The Garden State Gazette is using a pseudonym for the homeowner who first came forward. For the purposes of this article, we will refer to him as “Anthony.”

MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP, NJ – When Anthony bought his home through New Jersey’s affordable housing program three decades ago, the deal was simple and written in plain English:

- Buy at an affordable price

- Live there for 30 years

- Follow the rules, pay the mortgage, maintain the property

- Then, after 30 years, finally own the equity and be free to sell on the open market

That 30-year mark is now here for Anthony and his neighbors.

Instead of a long-awaited shot at full equity and financial freedom, they say they’re being told something very different:

Sign a new 30-year deed restriction — or else.

“This is not what we signed up for,” Anthony wrote in an email to The Garden State Gazette. “At the very moment we should finally have an opportunity to sell on the open market and maximize our equity, the township is seeking to impose another 30-year control period, without negotiation and without fair compensation.”

This article is the first in an ongoing Garden State Gazette investigation into whether New Jersey’s new “Round Four” affordable housing framework is being used to quietly lock long-time homeowners into permanent affordability they never agreed to.

The Statewide Ruling That Started It – And What It Actually Says

On March 20, 2024, Governor Phil Murphy signed P.L. 2024, c.2, a major overhaul of how New Jersey calculates and enforces municipal affordable housing obligations under the Fair Housing Act and the Mount Laurel doctrine. The law abolished the long-defunct Council on Affordable Housing (COAH) and created a new, court-linked framework to determine each town’s “fair share” of affordable housing from 2025–2035.

In September 2025, Mercer County Superior Court Judge Robert Lougy dismissed a lawsuit brought by 27 municipalities trying to block that law. The judge upheld the Legislature’s power to require towns to meet their Mount Laurel obligations and rejected arguments that the new law was unconstitutional or overreaching.

The message from the court was clear:

- Towns must meet their affordable housing obligations.

- The state can enforce that through the new framework.

Crucially, homeowners in Montgomery point out what the ruling did not say: it did not order towns to retroactively re-restrict homes whose original affordable-housing terms are expiring. The law does contemplate the possibility of extending affordability controls in some contexts—but as one statutory option to preserve units, not a blanket mandate to turn time-limited programs into de facto permanent ones.

From “New Construction” To “Cheap Credits”? Residents Say Town Is Taking a Shortcut

Under P.L. 2024, c.2, municipalities are supposed to plan for and deliver new affordable housing opportunities as part of a broader statewide system. That can include:

- New construction

- Inclusionary developments where private builders set aside affordable units

- Preservation of existing affordable units, subject to rules and minimum terms

The law also set a minimum 30-year deed restriction for new for-sale affordable units, and detailed how extended “preservation” terms can work for certain properties.

But homeowners in Montgomery say their township is stretching that concept beyond recognition.

According to residents, instead of:

- Approving new projects, or

- Forcing developers to include affordable units in future construction,

the township is allegedly leaning on a simpler, cheaper method:

Keeping old participants on the hook for another 30 years by unilaterally extending deed restrictions on long-time owner-occupants whose contracts are ending.

In other words, rather than adding new affordable homes to meet fresh obligations, residents say the township is trying to squeeze additional “credits” out of the same families who already did their 30-year time.

“We Played by the Rules. Now They’re Changing Them.”

Anthony and other homeowners describe a familiar pattern:

- They bought decades ago under clear 30-year terms.

- They lived in the homes, raised families, and maintained the properties.

- They paid mortgages, condo fees, and rising costs like everyone else.

- They did it all with the understanding that after 30 years, the restriction would end.

Now, as the end of that term arrives, they say a new agreement has appeared:

Sign this new 30-year control period — or face consequences.

Residents allege:

- The township, their HOA, and affordable housing administrator CGP&H are acting in concert to push homeowners into signing these new deed restrictions.

- CGP&H and local officials are threatening fines or penalties for those who refuse to sign.

- Homeowners are being told this is necessary to “comply” with the new state law — even though, they argue, that law was never meant to retroactively trap existing owners.

CGP&H (Community Grants, Planning & Housing) is a long-established administrative agent that manages affordable housing compliance for thousands of units in dozens of New Jersey municipalities. The company is approved by the Department of Community Affairs and widely used by towns to run waiting lists, certify incomes, and enforce affordability controls.

Homeowners are not disputing CGP&H’s general role in the state’s affordable housing system. What they are questioning is how that power is being used in this specific case — and whether it crosses the line from administration into what they describe as a “forced takeover” of their equity.

Who Wins, Who Loses?

From the residents’ perspective, the new setup creates a warped three-way dynamic:

- Developers benefit. They can continue to sell or build at market rates in a historically inflated housing market.

- Municipalities “check the box.” By counting extended restrictions on existing homes, towns may be able to report more affordable units without building new ones.

- Long-time homeowners lose. The very families the program was designed to help are the ones who, after decades of compliance, are told their equity is still off-limits.

For homeowners who planned to use their equity to:

- Fund retirement,

- Help children with college,

- Move closer to family, or

- Downsize to more accessible housing,

a surprise 30-year extension doesn’t feel like policy — it feels like a broken promise.

What the Law Says About Extensions — and Why These Homeowners Feel Misled

State law and related proposals do envision extending affordability controls in some contexts, particularly for preserved units and 100% affordable projects. A February 2025 bill, for example, discusses minimum 30-year terms for new deed-restricted units and lays out rules for extending controls so that original and extended terms can total at least 60 years in certain preservation scenarios.

But Montgomery homeowners say that wasn’t the deal they signed:

- Their original agreements, they say, promised a 30-year term, not a permanent or 60-year structure.

- They were never told at the outset that their homes could be unilaterally re-restricted for new statewide obligations decades later.

- They see a critical difference between owners voluntarily re-upping affordability in exchange for real compensation — and being told to sign or face penalties.

Legally, that tension — between written promises made to individual households and newer, broader statutory frameworks — is exactly the kind of conflict the state’s Affordable Housing Dispute Resolution Program was created to sort out.

But for now, this is playing out not in a courtroom, but in HOA notices, administrative letters, and tense conversations with residents who feel cornered.

December 1: Homeowners Plan to Speak Out

Residents say they’re done suffering in silence.

There is a public meeting scheduled for 6:00 p.m. on December 1 at the Montgomery Township Municipal Building, where this issue is expected to be discussed. Homeowners say they plan to:

- Ask township officials to explain, on the record, why long-time owners are being targeted for extended deed controls, instead of focusing on new development.

- Demand clarity on whether the new restrictions are truly required by state law — or simply a local policy choice.

- Request an end to what they describe as threats of fines tied to refusing to sign new agreements.

Several homeowners have already indicated they are willing to:

- Speak on the record,

- Share documents and correspondence, and

- Detail how this affects their retirement plans and financial futures after 30 years of compliance.

What’s Next

This is not just a technical housing question. It goes to the heart of trust between residents and the institutions that claim to serve them.

Key questions our investigation will continue to probe:

- Did original program documents clearly promise that deed restrictions would end after 30 years — with no unilateral extensions?

- Are current township and administrator actions consistent with P.L. 2024, c.2, or are they stretching “preservation” tools beyond what the Legislature intended?

- How many other New Jersey municipalities are using expiring 30-year owner-occupied units as an “easy” way to pad their new affordable housing numbers?

- What remedies, if any, are available to homeowners who believe their equity is being taken without fair compensation?

This article is Part One of The Garden State Gazette’s ongoing investigation into how New Jersey’s new affordable housing rules are being implemented on the ground — and who is paying the price.

If you are:

- A Montgomery Township homeowner affected by expiring deed restrictions,

- An affordable housing expert, attorney, or policymaker with insight into this issue, or

- A resident of another New Jersey town seeing similar patterns,

you can reach out to The Garden State Gazette tip line so this story can be fully and fairly told.

(“Anthony” is a pseudonym used only for this article to protect the homeowner’s privacy.)

*Developing story. This piece will be updated as more documents, responses, and testimonies become available.*

Update – Township Email Says Extension Is “Automatic” Even If Owners Refuse $10K After this article was published, Montgomery Township sent homeowners a written Q&A obtained by The Garden State Gazette. In it, officials state that owners “do not have to accept the $10,000 payment,” but that the affordability controls “will be extended automatically,” with the $10,000 going to the next purchaser instead. The email cites the original deed and Affordable Housing Agreement as the source of the Township’s right to extend, and links to new statewide UHAC rules – including section 5:80-26.26, “Municipal rejection of repayment option on 95/5 units” – as the legal backdrop for the change.

Member discussion